- Home

- Scott Martelle

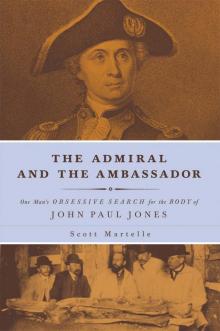

The Admiral and the Ambassador Page 6

The Admiral and the Ambassador Read online

Page 6

So it was a mixed group of passengers settling in as, with a flurry of horn blasts and cheers, a tugboat slowly pulled the St. Paul away from Pier 14 and out into the river. Porter was at the deck rail with everyone else, waving a small American flag as the gap between ship and shore slowly widened. The ship eased into the main channel and then turned under its own power and began heading south past Ellis Island, which just five years earlier had become the first landing spot for immigrants arriving in New York. A little farther along the ship passed the Statue of Liberty, fittingly on this morning, a gift from France a decade earlier. From there the ship steamed through the Narrows between Staten Island and Brooklyn and on beyond the spit of land that forms Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and then finally out onto the open ocean.

Over the next eight years, Porter would return to the United States just once. And when he finally sailed home for good, he would return with the body of an American hero.

4

Jones: The Scourge of England

NEAR THE END OF its voyage to Europe, when it reached a spot a few hundred miles southwest of England, the St. Paul steamed across an invisible line: the course followed more than a century earlier by a small fleet under the command of John Paul Jones.

Jones and his ships had set forth from the Île de Groix, off the south coast of Bretagne, France, before dawn on August 14, 1779. The Scottish-born American naval commander was aboard the warship Bonhomme Richard, accompanied by six other American and French ships. It was Jones’s second foray into British waters, and his intent was to seize as many British ships as he could in the name of the Continental Congress and bring the violence of the American Revolution to England herself.

As a military maneuver, Jones’s efforts didn’t have much effect on the war. The psychological effect, though, was considerable. Jones, in the earlier sortie, had invaded the port of Whitehaven, the first time a foreign force had attacked a British port since 1667. His men had also raided the mansion of the Earl of Selkirk, making off with the family silver. So the presence yet again of Jones and a fleet of mismatched warships off the British coast stirred the island with fear. While the excursions would cement Jones’s reputation for skill and cunning at sea and help establish him as the father of the US Navy, to the British, Jones was a pirate, and his return to the land of his birth at the helm of an American navy ship was viewed as an act of treason.

Jones was born July 6, 1747, in a worker’s cottage on the Arbigland estate near Kirkbean in southwest Scotland, overlooking the Solway Firth, which separated Scotland from England. His name then was the same as that of his father, John Paul (the son would add “Jones” later), a gardener for the Craik family. Jones was the fourth of seven children, though only five survived into adulthood.1

The details of his early schooling are murky, but at age twelve Jones moved across the firth to Whitehaven, the port he would later attack, to apprentice himself to merchant John Younger, who handled trade with the American colonies. Dumfries, the market town closest to where Jones was born, was also a major hub for tobacco imports, so the region had a steady and deep relationship with sea trade. Jones’s oldest sibling, William, had already followed the trade route to Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he made his fortune as a tailor and local businessman.2 Jones, though, was as much interested in the way the goods moved as in the trade itself. As a child, he watched ships ply the Solway Firth and later taught himself celestial navigation. He made his first transatlantic crossing at age thirteen aboard one of Younger’s ships, but the next year Younger went bankrupt and Jones was cast out on his own. He spent the next few years moving from ship’s crew to ship’s crew, sailing between England and the West Indies and also several times to Africa on slavers before giving it up for more conventional trade.

In those early days of his sailing life, Jones saw the sea as a means to an end. As he picked up experience, he began to map out a future that did not involve the sea. He hoped to amass enough of a fortune to buy land, maybe near his brother in Virginia, by the time he reached thirty. Given the arc of Jones’s career, though, it seems that while he might have yearned for a stable life as a landowner, he gravitated to the sea, and eventually to the salons of powerful men and beautiful women. One suspects that had Jones joined his brother and become a Virginia tobacco grower, he would have died of boredom. And it’s hard to tell whether his desire to settle on a farm was a life plan or a dream he ultimately lacked the desire to fully pursue.

Regardless, Jones was adept at playing the hands he was dealt. In July 1768 Jones was in Kingston, Jamaica, and unattached to a ship. He was offered transport back to England as a passenger aboard the John, captained by Samuel McAdam, who was from the small port town of Kirkcudbright in the same part of Scotland in which Jones was raised. (He and McAdam likely knew each other.) En route to Liverpool, McAdam and the first mate—the only members of the crew who knew how to navigate—died of illness at sea. Jones, just twenty-one but an accomplished navigator, took command and brought the ship safely to port, earning the gratitude of the owners and two more assignments skippering the John to the West Indies.

Jones proved to be a remarkably precocious seaman, though his mercurial personality created troubles. In 1770 the carpenter aboard the John got so deeply under Jones’s skin that he had the man, Mungo Maxwell, tied to the rigging and flogged. Once moored in Rockley Bay at Tobago, Maxwell went ashore and pressed charges. Jones was cleared by a judge who saw nothing criminal in Maxwell’s scars. Maxwell, though, was done with Jones and the John. He booked passage back to England via another ship but died en route. When word of the flogging and the apparently unrelated death reached Maxwell’s father in Kirkcudbright, he pressed charges. Once the John arrived from the West Indies, Jones was imprisoned until he could arrange bail. Still, few in Kirkcudbright gave much weight to the charges, and Jones remained free on bond with the case in limbo. Six months and a trip to Tobago later, Jones obtained copies of the judge’s records and the charges in Scotland were dropped.3

The realities of life at sea meant that to succeed, a captain had to be tough but fair. Too lenient and he would lose control of the crew. Too strict and a captain might find himself killed or set adrift by a mutinous crew. Over his career, Jones developed a reputation not only for toughness but also for seamanship. He was often disliked by peers because of his arrogance and petulance and by some of his crews for his tempestuous and authoritarian nature. Yet sailors also admired him for his abilities at sea, and his success in trade—the crews received a cut. Still, his arrogance caused him occasional troubles.

In October 1773 Jones was captain of the Betsy, in port at Scarborough, Tobago, to sell a cargo of wine and other supplies, intending to reinvest the proceeds in cargo for the return trip to England. He decided to withhold his crew’s wages while in port to increase the amount of goods he could buy for the return trip. Many of his crew members, though, were Tobagonians, and they wanted their wages while in their home port. One seaman in particular took umbrage, and after some harsh words, began to steal one of the ship’s tenders to take himself ashore. Jones brandished a sword in hopes of intimidating the man. Instead, it drew him out, and the seaman went at his captain with a bludgeon. Jones ran him through with the sword, instantly killing the crewman. In Jones’s version of the events, related in a March 1779 letter to Benjamin Franklin, he painted a questionable scene in which the crewman impaled himself on the sword as Jones held it in front of him, a story akin to a child claiming that a purloined piece of candy jumped into his pocket on its own.

Jones turned himself in to the port authorities, viewing the killing as an act of self-defense for which he would be cleared at trial. Acquaintances in port persuaded Jones that the chances of acquittal were not all that strong and that a lynch mob convened by the dead man’s friends was not out of the question. That night, after entrusting most of his money and other holdings to a friend, the Scottish captain slipped across the island on horseback, boarded a different ship, and set sail

with fifty pounds in his pocket and a new name: John Paul Jones.4

Jones disappeared for a few months, eventually surfacing in Virginia around the time that his older brother, the tailor, died. (The estate went to a sister in Scotland, rather than to his estranged wife; Jones was left nothing.) Over the next few months, Jones stayed nearby with a friend, Dr. John K. Read, and courted Dorothea Dandridge, daughter of a wealthy Virginia family. He lost that prize to plantation owner and widower Patrick Henry, soon to become governor of Virginia.

The rebellious mood in the colonies was growing, and tensions with England were increasing. In an effort to isolate the problem, the British barred trade between the colonies and the West Indies, which meant the money Jones had left in trust in Tobago was out of his reach. In April 1775 gun battles broke out between colonists and British soldiers at Concord and Lexington in Massachusetts. In October the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, ordered the creation of a Continental army and a Continental navy.

Jones, low on cash and seeking work, traveled to Philadelphia to offer his services. Though he later wrote that he was moved by the pursuit of liberty, not cash, the words ring a bit hollow given how little Jones had engaged with political thought and debate previously and how energetically he had pursued trade in his quest to retire from the sea by age thirty. It was a large part of his personality to play up the best parts of himself while ignoring the negatives. Failures were the fault of others; successes were his and his alone. Friends such as Benjamin Franklin warned Jones that his petulance, complaints, and transparent grasps for glory were alienating, and not helping his cause with fellow revolutionaries. Jones sought over time to rein himself in and be more magnanimous in doling out credit for victories at sea, but he usually fell short.

Whatever Jones’s motives in traveling to revolutionary Philadelphia, on December 3, 1775, he won an early commission as first lieutenant aboard the Alfred, and his ambitions for a quiet retirement as part of the Virginia landed gentry rapidly faded.

The Continental navy never quite got its sea legs. Between the creation of the navy in October 1775 and the signing of the peace treaty in Paris in 1783, the Continental navy took control of fifty-seven ships through purchase, construction, loan, or seizure. Of those, thirty-five were captured, sunk in battle (some scuttled to avoid capture), or lost at sea.5 Some of the American captains seized British merchant and warships as prizes, but they did not affect the trajectory of the war, although French warships in 1781 helped George Washington defeat Lord Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown, the last major battle of the Revolution.

Still, the navy gave Jones the chance to shine. The plan for the American sailing force was to hassle the British fleet and interfere with British commerce at sea. Aboard the Alfred, Jones served under Captain Dudley Saltonstall, a man Jones intensely disliked. After a foray to the Bahamas with a small fleet of four ships under the command of Commodore John B. Hopkins (they managed to capture some munitions but let a cache of gunpowder slip away and botched an attack on the HMS Glasgow on the way back to port), Jones was given command of his own ship, the sloop Providence, on May 10, 1776.

His abilities quickly became apparent. Jones’s first few trips involved ferrying George Washington’s troops or escorting merchant and supply ships. On August 6, 1776, Jones received orders from the Congress’s Marine Committee that effectively unleashed him on the seas to wreak whatever havoc he could on British navy and merchant ships. Jones had a crew of about seventy men, which made quarters quite crowded. It was a necessary overpacking, though: Jones needed skilled and trustworthy seamen in reserve to command whatever ships he might capture as prizes and sail them to friendly ports where the spoils would be accounted for. The Providence set sail on August 21, and less than a week later it had seized the British whaler Britannia and sent it under a prize crew to Philadelphia.

The Providence was sleek and nimble, and combined with Jones’s shrewd sailing skills, it was able to elude British warships. Over a span of forty-nine days he captured seven ships and scuttled or burned several others, most of them British fishing or trade boats. He had trouble—as did other captains—keeping his crew, though, because the privateers who worked independently of the navy offered more money and a larger split of the spoils from captured ships. Disputes over pay and percentages raged for years—the US Congress would receive bills from descendants of the sailors well into the mid-1800s.

On October 17, 1776, Jones was given the command of the Alfred, the ship on which he had served as a lieutenant, and ordered to sail for Canada to rescue captured American sailors pressed into service at a British coal mine. Jones captured several ships on the way and learned from the crew of one of them that the Americans no longer needed rescuing because they had joined the British navy. To add to the failure, the British managed to recapture nearly all of the ships Jones had taken.

Jones spent the winter in Boston as the Continental Congress’s Marine Committee rearranged its navy. Despite Jones’s seniority—he was the fourth man commissioned—and his skills as one of the force’s best and most effective captains, Jones lost out in the politics of the moment. The navy was rushing to build or refit existing ships as warships, and the work was being done at a range of ports. Jones had little history in the United States and only a few friends—political, military, or personal. As the assignments for the enlarged fleet were doled out, Jones found himself ranked eighteenth, which meant someone else would be assigned to the Alfred while he was returned to the smaller sloop Providence, his first command. Part of the problem was that the Marine Committee sought to pay political favors and so assigned captains in or near the ports where the ships were being built.

Jones took the news poorly, sending off angry letters and denunciations of some of his fellow captains to the Marine Committee and the president of the Continental Congress, as well as his own friends and his two main backers, Robert Morris and Joseph Hewes. Morris was a key figure in the financing of the Revolution and overseer of the Continental navy, and Hewes of North Carolina had a business partner with roots in Kirkcudbright. “I could heartily wish that every commission officer was to be previously examined,” Jones wrote bitterly to Morris. “For, to my knowledge, there are persons who have already crept into commission without abilities or fit qualifications.”6

Ultimately, Jones was saved the ignominy, as he saw it, of being sent back to the ship upon which he began as a captain in the Continental navy, though he never forgot the perceived slight. His friend Morris, with the support of John Hancock and others impressed with Jones’s early successes, decided in February 1777 to give the Scotsman command of the Alfred and direct him to lead a fleet of four other ships with orders to sail south to harass the British navy in the West Indies and the Gulf of Mexico. That assignment hadn’t yet begun when, after some more vacillation, it was rescinded, and Jones was given command of the new twenty-gun sloop of war Ranger after its previously assigned captain, John Roche, “a person of doubtful character” in the words of a Congressional resolution, was booted out of the navy for malfeasance.7 It was the same day the Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes as its new flag, and Jones would long make note that, as biographer Morison phrased it, “the most glorious part of Paul Jones’s career in the Navy began on the birthday of the Stars and Stripes.”8

A shipyard in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, owned by John Langdon, was building the Ranger, and Jones traveled there in July to oversee the final construction and to begin outfitting it with supplies and a crew. It was a small town, like most of the colonial villages, and Jones became a familiar figure bargaining with merchants over supplies, discussing the ship’s progress with Langdon, and, one presumes, making the rounds of the dinner tables of the city’s non-Tories. Jones experienced some frictions with some of the merchants and with Langdon, caused primarily by Jones’s exacting standards and his lack of diplomacy when not getting his way. That Langdon was a hard-driving and hard-headed shipbuilder didn’t help. They squabbled t

hrough the summer over matters both serious—how many cannons to install and the mast configuration—and minor, such as whistles for the boatswains (Langdon thought they should just yell orders).9

Jones’s orders were to sail the Ranger to France and be outfitted there with yet another ship to sail back to America. (After at first balking, so as to avoid an entanglement with the British, France was now beginning to aid the revolutionaries directly.) By November 1, the Ranger was ready, and Jones set sail. A month later, after a challenging crossing of the stormy North Atlantic, the ship arrived at the mouth of the Loire. Once in port, Jones discovered that the Dutch-built ship he was expecting to take over was caught up in a diplomatic row between the French and the Dutch. So Jones stayed with the Ranger, spending the rest of the winter refitting the ship and waiting for the weather to break. And he received orders that must have gladdened his heart: a blank check from his superiors to engage in whatever sorties he thought would best help the revolutionary cause, whether on sea or land.

In early February, Jones set sail in the Ranger along the French coast, acquainting himself with the waterways. He put in at Quiberon, on the south coast of Bretagne, and upon his arrival, Jones exchanged a traditional naval salute with a French ship leading a small squadron of escorts for commercial vessels preparing to leave France. Jones’s Ranger was flying the new Stars and Stripes, and the exchange of ceremonial fire marked the first time the new flag of the fledgling United States of America was saluted by a foreign power.

The Admiral and the Ambassador

The Admiral and the Ambassador